Footage from police cameras not only protects citizens, but officers as well. That’s why one local politician wants every force in the state using them.

The video speaks for itself. Taken from the dashboard camera of a Washington Township police officer’s patrol car, the footage shows Assemblyman Paul Moriarty performing a field sobriety test in a Chick-fil-A parking lot after a patrolman pulled him over in June 2012. Officer Joseph DiBuonaventura is heard on camera saying he stopped the legislator and former Washington Township mayor for cutting the officer off. But that’s not what happened, and the footage proved it.

The improper traffic stop—caught on one of the few patrol car cameras in Washington Township—is what led a Gloucester County prosecutor to drop the resulting drunken driving charges against Moriarty. The officer has since been indicted for criminal misconduct and falsifying a police report.

Moriarty says if it weren’t for that video, it’s likely that no one would have believed that the officer was unjustly targeting him by stopping him for no reason and then charging him with driving under the influence.

“I started thinking, ‘My goodness. What would have happened had this cop car not had a camera in it?’” Moriarty says. “It’s 2014 and there are cameras everywhere. You’d think police cars that gather evidence for court would have cameras as well.”

But not all patrol cars in his hometown—or in South Jersey—are equipped with video. A bill proposed by Moriarty would gradually change that by allowing municipalities to collect a $25 surcharge from all DUI offenses to put toward the cost of buying and installing cameras for any new or used patrol cars purchased each year. Or, the department could buy body cameras for their officers to wear—a more affordable option, Moriarty says. The proposal was approved by both the Senate and Assembly in late 2013, but Gov. Chris Christie declined to sign it into law, pocket vetoing it with no explanation. The bill was reintroduced in early February with the hopes of setting a standard for all law enforcement in New Jersey to follow.

Some towns in South Jersey are already ahead of the game. Both Cherry Hill and Evesham townships equip all of their police cars with video cameras. Not only do they capture footage when an officer may be in the wrong, but they also exonerate police if citizens make a false claim against them.

In Cherry Hill, police cars have been equipped with cameras for the past eight years and the department is now working on upgrading the technology to be completely digital, says Sgt. Richard Humes. There are a lot of benefits of having video cameras, Humes says. “The primary one is for court. You can go in and, instead of having an officer testify, you can simply present video evidence that shows and backs up the officer’s report. It does wonders in cutting down on officer complaints.”

Microphones attached to the officer’s shirt or duty belt also record audio when they step out of the car. However, there are limitations to video. “You may not get the entire incident on video because it moves out of the camera’s range,” Humes says.

That issue is why Evesham’s police department is taking its cameras one step further.

Come summer, every township police officer will be equipped with a body camera, says Lt. Joseph Friel. Ever since vehicle cameras were installed in 2000, they have proven themselves invaluable, Friel says.

“We owe it to the public in accountability and it goes both ways. We owe it to our officers. It’s not just his word or her word. Same thing if an officer does something wrong,” Friel says. “The car cameras were so successful, but you lose a little bit if an officer has to go chase someone or goes into a house for a domestic. You’re not capturing that.”

The township is bonding $50,000, paid over the course of five years, to equip every officer with a body camera. The cost includes the hardware—a small device mounted to the officer’s chest—as well as software and data management at the station.

And there hasn’t been any resistance from the officers. “(Cameras) are such a part of our daily operation here that, even through our field testing of body cameras, we haven’t had any negative comments. Everyone in law enforcement sees it’s coming. This is obviously the next step,” says Friel.

Larger police forces throughout the country are going this route, such as New Orleans and Los Angeles, and even Atlantic City. But for most departments, the issue comes down to money. The Office of Legislative Services estimates the cost to towns would be higher than the revenue they’d gain from the surcharges. Based on the average number of DUI convictions the past three years—there were 22,150 in 2012—the surcharge would bring in about $575,000 in additional funds statewide per year, according to the estimate.

The cost of each in-car camera could range from $3,000 to $8,000—less if it’s a body camera, Moriarty estimates.

The New Jersey League of Municipalities “recognizes the benefit of such systems” but won’t support a state mandate if it’s not fully funded, says league Executive Director William Dressel. “In many cases, it just comes down to dollars and cents. Many towns have been laying police officers off and if it comes down to whether you hire a police officer or put a camera in a car, they have to look at it from that standpoint,” he says. That’s been the case in Washington Township, according to police Chief Rafael Muniz.

As police officers retire, those vacancies aren’t being filled, and even though Muniz has budgeted for additional patrol cars the past few years, they haven’t been allotted the funds to buy them. Currently, less than 10 cars in the township are outfitted with cameras.

“I think they’ve been invaluable,” Muniz says, noting how the cameras have assisted on the scene of a crash or during internal affairs investigations. “If you have a camera, the investigation can be completed in 10 to 15 minutes. If not, you can spend a week interviewing people.”

Body cameras would be less costly, according to Muniz, but it may take the officers—and the public—some time to get accustomed to them. “When we first instituted car cameras, many officers were hesitant. They thought ‘Big Brother’ was watching, but now they’re kind of used to it and they’ve seen the benefits of the cameras. It would be a change in culture, but it seems to be the direction many departments are going.”

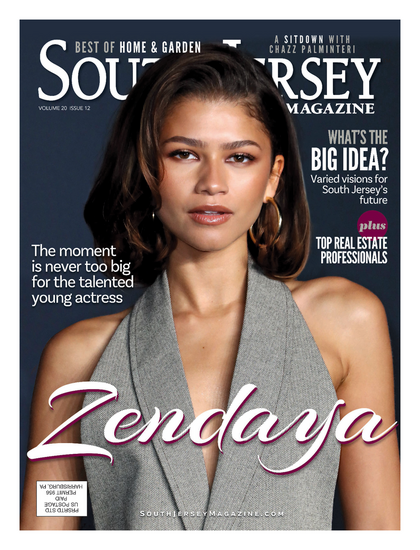

Published (and copyrighted) in South Jersey Magazine, Volume 10, Issue 12 March, 2014).

For more info on South Jersey Magazine, click here.

To subscribe to South Jersey Magazine, click here.

To advertise in South Jersey Magazine, click here.